Green tea is synonymous with China and Japan, but the green teas coming from these two countries are dramatically different in look and taste. Today green tea comes for several countries, but is always referred to as a Chinese or Japanese processed or styled tea. In general, Japanese teas are processed using steam to denature the enzymes found within the tea to prevent it from losing its green color; while in China, heat is applied through pan firing. These two distinct methods produce teas that have completely different character.

CHINA

Green tea was first developed in China during the Yuan Dynasty (1280–1368). Tea growers were looking to produce a tea that was milder overall, with less bitterness. They developed a process called chaoqing, which translates to “roasting out of the green.” This pan fired method de-enzymed the tea leaves, which radically changed the profile of the tea. This new tea had less bitterness, improved flavor, and an attractive appearance with a pleasing color. These traits were highly sought after by Chinese tea consumers. However, with packaging technology lacking, green teas could not travel far, as their quality would not hold up. Just about every tea region was producing a type of green tea with different production techniques. This led to the array of green teas that are available today. Luckily for us, technology caught up over the centuries so that everyone can enjoy these wonderful teas.

Though production processes have been refined over the years, most Chinese green teas go through the same processing steps. The region that the tea is grown and processed in, is what makes each of these green teas taste different.

Plucking » Withering » First Pan Firing » Shaping » Second Pan Firing » Final Firing » Sorting

For green tea, there are five notable growing regions in China –Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, Anhui, and Henan. Zhejiang Province, an eastern coastal province of China, produces Dragonwell, Gunpowder, and Tian Mu Qing Ding. The southern province of Jiangxi produces Lu Shan Yun Wu green tea, which is not as popular in the States. But Jiangxi Province played an important role in the spread of tea knowledge. It is here that Japanese monks came to study Zen Buddhism and share tea and the tea ceremony which became chanoyu. Jiangsu Province, positioned along the Yellow Sea coast, produces Bi Luo Chun green tea. Land-locked Anhui Province produces Mao Feng and Luan Guapin. Henan Province, which is located in central China, is famous for its Mao Jian.

Dragonwell green tea is known for being both a mythical tea and one of controversy, as more Dragonwell tea is consumed each year than is actually produced in the West Lake Region. Legend tells us that in 250AD, a Taoist monk told farmers, desperate for rain, to pray to the dragon who lived in a nearby well. When the rain came quickly, the well became famous. Today, the Dragon Well Monastery still stands next to the well.

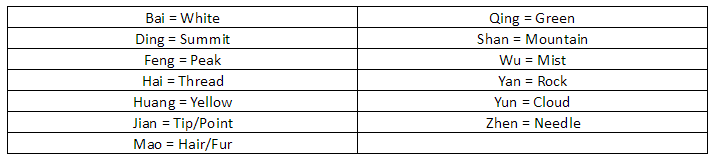

Consumers are often afraid of Chinese tea names, but if you know just a few of the words, you can easily see that they often consist of single words strung together to indicate the shape and origin of the teas.

JAPAN

In Japan, tea is much more than just a beverage. It is an integral part of the culture and is a symbol of hospitality. Though references to tea can be traced back to the early 800s, it wouldn’t be until the 1100s that tea production began, and not until the 16th century before tea production really took off. Back then, sencha referred to all boiled infused teas, while today, sencharefers to a high-quality spring harvest tea.

Almost all of the tea produced in Japan is some type of green tea. However, there are 2 main categories of tea produced. The difference is in the growing and cultivating of the bushes; either in full sunlight or shade. Shade grown teas include matcha, gyokuro, karigane, and kabusecha. Full sun grown teas include sencha, bancha, shincha, kukicha, genmaicha, tamaryokucha, and hojicha. Due to the stress that the leaf has been put through, shade grown teas have a unique taste profile. They produce higher concentrations of chlorophyll, theanine amino acid, and caffeine, which produces a tea with less astringency, more body, and a rich umami flavor.

Production in Japan is also unique in that there are two distinct stages. The first stage, called aracha or crude tea, allows tea growers to harvest their tea in the spring, when the tea is at its best, and then store it until it is needed throughout the year. This first stage consists of:

Sun/Shade Cultivation » Plucking » Steaming » Shaping » Drying » Storing

It is important to note that most of the plucking in Japan is done my machines that are highly advanced and can select only the bud and leaves that are needed. However, some of the more expensive higher quality teas are still hand plucked.

The second stage, which completes the tea, is referred to as refined tea production. The second stage consists of:

Firing » Sorting » Blending

Blending in Japan is slightly different, as it is very common to get tea leaves of varying sizes in a premium grade tea. Unlike teas from China, the look of the leaf is not as important as the taste in the cup.

There are five main growing regions, or prefectures, in Japan. The most well-known region is Uji in the Kyoto Prefecture. Uji is considered to be the birth place of Japanese tea, even though it doesn’t produce a lot of volume. Other regions include: Shizouka Prefecture, Kagoshima Prefecture, Mie Prefecture, and Fukuoka Prefecture. Shizouka Prefecture produces about half of Japan’s overall tea volume. Fukuoka Prefecture produces more than half the countries volume of Gyokuro tea.

Though the largest producers of green tea today are still China and Japan, green tea is produced in several countries. While each differs in processing methods and taste, all growing regions of green tea follow one of the two processing methods, which are considered the green tea standards for the world.

Art of Tea is an award winning purveyor of specialty and organic teas, based in Los Angeles, CA.

If you found this article helpful, please share it with coworkers, colleagues, and fellow lovers of tea.